One of my favorite types of algorithms in computer science is recursive backtracking. By following a shockingly simple procedure, you can solve complex problems in reasonable amounts of time, with no bookkeeping.

As a practical example, I’ll walk you through an example solving Sudoku puzzles with the lingua franca of programmers, C.

We know that Sudoku is a 9 x 9 number grid, and the whole grid are also divided into 3 x 3 boxes There are some rules to solve the Sudoku. We have to use digits 1 to 9 for solving this problem. One digit cannot be repeated in one row, one column or in one 3 x 3 box.

A recursive backtracking algorithm follows a really simple formula:

- Find a possible solution. If out of possibilities, go up a level.

- Move to the next cell.

- ????

- PROFIT.

Dev C 2b 2b Sudoku Codes

Solving Sudoku, One Cell at a Time

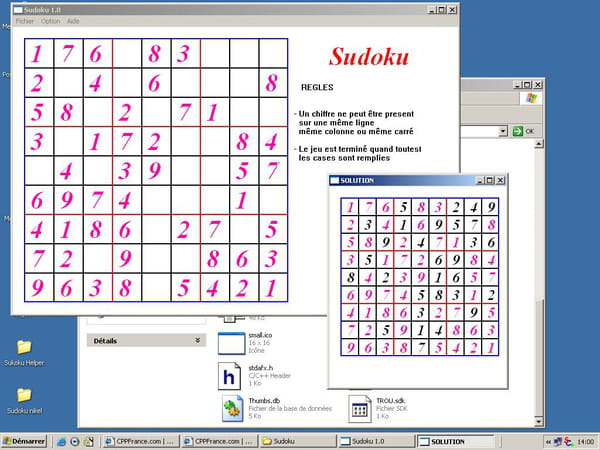

Let’s start out with our particular problem, the game of Sudoku. Sudoku is a logic puzzle in which you are given a 9×9 square of numbers, divided into rows, columns, and 9 separate 3×3 sectors. In each row, column, and sector, the numbers 1-9 must appear. At the start of the puzzle, just enough of the grid’s elements are filled in to guarantee only one unique solution based on these rules.

The way most humans go about solving these puzzles is by use of logic. By careful inspection of the positions of the numbers in the grid, you can use the rules of the game to eliminate all possibilities but one, which must then be the correct number. For example, in the puzzle above, we know there must be a 7 somewhere in the top middle sector. Because there is a 7 in column 5 and one in column 6, it can be deduced that there will be a 7 in column 4 of the top middle sector. Since the top two rows of that column are occupied already, the third row will contain a 7.

This method of problem solving can be extremely rewarding for a human, but is error-prone and slow. The extremely simple set of rules for a Sudoku solution make the definition of a solution simple, allowing for easy solving by a computer. We’ll apply a recursive backtracking algorithm to get the computer to do all this hard work for us.

We’ll start by defining the traversal order. Begin by assuming there’s some magical function isValid in existence that will tell us if a number is valid in a square or not.

If you’ve got sharp eyes, you may notice immediately that this function will recur infinitely (until we segfault). We’ll get back to that in a moment. First, make sure you understand how this traverses the puzzle. Each function call will move to the next square of the puzzle after stuffing a valid value into its own square. After 81 recursive calls, the entire puzzle has been filled. If, at any point, all numbers 1-9 have been tried for a square, the cell is reset to 0 and we return with a non-truthy value to keep trying at the next valid place up the stack.

We still need two more things in this function: a successful termination condition and something to skip over the squares that have already been filled in. Let’s add those now.

Now, we check for a truthy value in the Sudoku puzzle before we start modifying it, allowing us to continue without clobbering the given hints. We also actually return a truthy value of 1 if we reach the row index ‘9’, meaning we’ve successfully placed a value in every row of the puzzle.

One more thing remains, and that’s to actually implement our magic isValid function. This just needs to directly check the rules of Sudoku. We need check the value passed in for uniqueness in the row, the column, and the sector. By checking the row and column, there are only four squares left in the sector needing checking. We’ll use some modulus operator magic and a for loop to get this to happen.

That’s about it. To solve a Sudoku , you now only need to pass your puzzle in as a 9×9 array of ints with row and column set to 0. The recursive solver will crunch away and either return a 1, indicating that the Sudoku has been solved correctly and the solution is on the stack, or 0, indicating the Sudoku had no valid solution.

Recursive Algorithms for Better Problem Solving

The term recursive backtracking comes from the way in which the problem tree is explored. The algorithm tries a value, then optimistically recurs on the next cell and checks if the solution (as built up so far) is valid. If, at some later point in execution, it is determined that what was built so far will not solve the problem, the algorithm backs up the stack to a state in which there could be another valid solution.

Due to the way that we pass the puzzle between calls, each recursive call uses minimal memory. We store all necessary state on the stack, allowing us to almost completely ignore any sort of bookkeeping. This lack of bookkeeping is by far and away my favorite property of this algorithm.

While there have been some very fast Sudoku-solving algorithms produced, a basic backtracking algorithm implemented efficiently will be hard to beat. Even a sudoku puzzle designed to defeat this algorithm runs in less than 45 seconds on my aging laptop. My full implementation can be found here, and should compile in pretty much any C compiler.

Hopefully I’ve been able to interest you in the possibilities of what appears to be a neglected class of algorithm, recursive backtracking. While many people seem to be afraid of recursion, it is an incredibly powerful way of solving problems. There is virtually no bookkeeping, extremely minimal memory usage, and a very reasonable runtime for a problem that generalizes to be NP-Complete.

Dev C 2b 2b Sudoku Code Answer

To learn more about recursive backtracking algorithms, check out the excellent Stanford Engineering Everywhere videos. You can also read Peter Norvig’s awesome page on Sudoku solving, which uses a similar approach.